Stigma in the system: Experiences of the UK social security system

This research examines how stigma is produced, reinforced, and experienced in the UK social security system.

- Published

- 24/09/2025

Introduction

The Stigma in the System report, from University of Bristol’s Personal Finance Research Centre, was commissioned by Turn2us and generously funded by Royal London as part of a long-term strategic relationship. This summary outlines the report’s findings on how the experience of accessing support impacts claimants and the overall effectiveness of the system.

You can read the full research report here.

Based on what we learnt from this research, we have published a policy report outlining what the government needs to do to create a social security system that promotes dignity, independence, and opportunity. Find out more about our policy recommendations here.

Turn2us is a national charity that helps people experiencing financial insecurity to access the support they’re entitled to and advocates for a system built on dignity, fairness and trust. Turn2us work alongside those with lived experience, developing tools, grants, and services to support them.

Executive summary

Stigma in the UK social security system is more than a matter of hurt feelings, it has deep and measurable consequences for individuals, communities, and the system itself. It can push people to delay or avoid claiming the support they are entitled to, worsening financial hardship, fuelling debt, and undermining health and wellbeing.

For government and society, this can mean higher downstream costs in healthcare, social services, and crisis support, alongside the economic losses of reduced participation in work and community life.

Stigma operates in multiple, overlapping ways: through the way the system is designed and delivered, through public attitudes and media narratives, and through the internalisation of negative stereotypes by those who need support. These dynamics not only damage individual lives but also erode trust in the social security system, making it less effective as a safety net for everyone.

This research examines how stigma is produced, reinforced, and experienced in the UK social security system; how it shapes perceptions and behaviours; and what this means for financial security and wellbeing. We explore its drivers, its impact on both claimants and non-claimants, and the changes needed to create a system that supports people with dignity and fairness.

Methodology

- Secondary data analysis of the British Social Attitudes survey (from 2012-2023). This is an annual cross-sectional survey of between approximately 3,000 and 6,500 UK adults, capturing (among other things) attitudes to welfare and benefit claimants. We use this data to explore trends in attitudes over time.

- 25 online semi structured in-depth interviews with claimants of any age who have experience of the benefits system (sample size of 13), non-claimants on low incomes (sample size of 6), and those working in the welfare advice sector (sample size of 6).

- A nationally representative online survey of 4,000 UK adults exploring perceptions of the social security system and the experiences of those who claim benefits. The survey was distributed via YouGov’s nationally and politically representative panel in June 2025.

Key findings

Stigma and the social security system

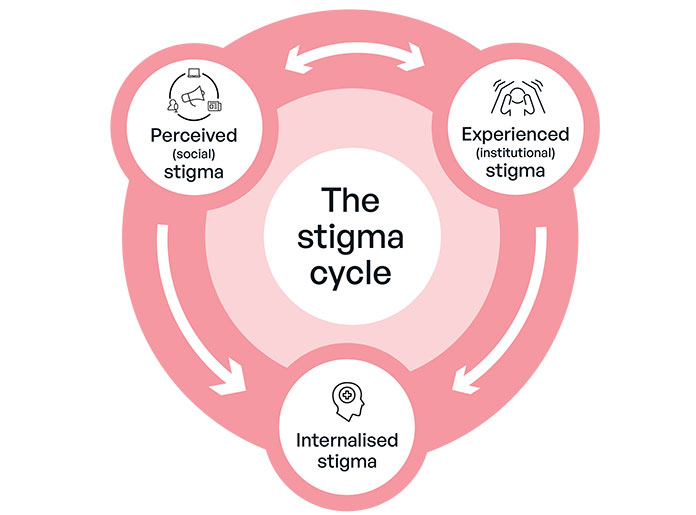

Stigma is built into how the system operates, reinforced by social narratives, rules, and everyday experiences. This research identifies three types of stigma:

- Perceived stigma is where claimants are aware of societal and media stereotypes portraying benefit claimants negatively

- Institutional stigma exists within the benefits system, such as hostile treatment by staff and intrusive assessments, which reinforce negative perceptions

- Internalised stigma leads claimants to feel ashamed or worthless, impacting their self-esteem and causing anxiety.

These elements reinforce each other, influencing how the institutional stigma produced within the social security system shapes wider, perceived stigmatising views around benefit claimants.

Together, they help form societal beliefs around benefits, which can then lead to claimants and potential claimants internalising these views, which affects how people interact with the system.

Stigmatising experiences within the system

Qualitative interviews and survey results demonstrated that navigating the social security system is difficult, overly complex, and demoralising, potentially traumatising.

I don't particularly trust any of it, and the sooner I'm out of the system, the better for me. As soon as I can go back to work full-time and not be dependent upon because I hate being dependent upon the system. Because I do feel like your life is in somebody else's hands and I know they can stop the money at any stage if they wanted to for no reason. So yeah, I just hate it.

Suspicion and control related to conditionality in benefits and PIP assessment

- 64% of current claimants felt the benefits system was trying to 'catch them out'.

- 49% felt they were made to feel undeserving of money.

- Only 22% felt the application process was easier than expected, while 47% disagreed.

Institutional stigma in the benefits system arises from practices that prioritise fraud prevention and compliance over meaningful support. Claimants felt treated with suspicion, subjected to intrusive monitoring, rigid rules, and frequent rejections, undermining trust.

Conditionality and sanctions further depersonalised the process, forcing people into "tick-box" exercises rather than genuine help. Supportive approaches during the Covid-19 pandemic showed potential for a more person-centred system, but currently, many claimants experienced stress, mistrust, and loss of autonomy.

Procedural rigidity, dismissive attitudes, errors and uncertainty

Our research showed a lack of flexibility in accounting for individuals' circumstances not aligning with predefined categories. This happened during work coaching, where tailored support should be offered. Of those recalling work coaching, only 15% said it had been very or quite beneficial.

Some DWP staff appeared inadequately trained, belittling claimants and making unhelpful suggestions. The attitude of the staff may be self-defeating as one claimant felt this attitude could have put her off getting back into work, as she felt she ‘wasn’t good enough for anything’.

She was like, ‘so have you made a CV?’ and I literally looked at her, and I said, ‘I worked in recruitment for seven years, please don't ask me if I've made a CV’. I said if you spent 30 seconds getting to know me, then you would know my previous history.

- A quarter (26%) of current claimants felt DWP made errors handling their claim, while 28% disagreed.

- 42% agreed that staff assessing their application lacked empathy.

Errors and experiences of trying to rectify them were considered disempowering. Applying for Universal Credit was easier but resolving issues could be difficult and time consuming, with claimants subject to rude treatment from DWP staff.

- 67% of all current claimants agreeing with the statement: "I often worry that my benefits could be taken away from me in future."

- This rose slightly to 73% among current UC claimants, but even more so among PIP claimants (80%).

The PIP assessment was considered dismissive, with assessors misrepresenting what happened or was said during the assessment process. Claimants felt the assessor did not believe them.

Some of it wasn't even true, like she had basically lied by saying I had made my own way there when that wasn't even asked, and I hadn't made my own way there. My husband had taken me.

The system was unreliable and uncertain, with:

- Half (50%) of current claimants found it difficult to know what benefits they might be eligible for.

- 57% of those who had experienced errors or issues with the DWP struggled to get these resolved.

Complexity and difficulty

Claimants often reported difficulties when making initial applications (38% of current claimants found this ‘very’ or ‘quite difficult’) and when updating the DWP on changes to their circumstances (28%).

Other stages of the process were even more challenging. The most difficult involved filling out the PIP application form (82% of PIP claimants), undergoing health assessments by Independent Assessment Providers (76%), and appealing DWP decisions (63% of current claimants).

Those who were currently claiming health-related benefits (such as PIP) were more likely to find each stage of the process difficult than those solely claiming low-income benefits, such as Universal Credit.

For example, two-thirds (65%) of those receiving only health-related benefits found appealing the DWP’s decision a difficult experience, as opposed to 49% of those only receiving low-income benefits.

The impact of stigma

Stigma can have a material impact on the lives of people who do or should claim. It may mean that people either don’t claim at all or delay making a claim because they feel ashamed or embarrassed, which can exacerbate financial insecurity. Applying for benefits can have a negative emotional impact on self-esteem and affect both mental and physical health.

Despite this, public attitudes indicate support for a fairer approach. The majority (71%) believe claiming benefits should not be shameful, and 79% would encourage a loved one to apply if they needed support.

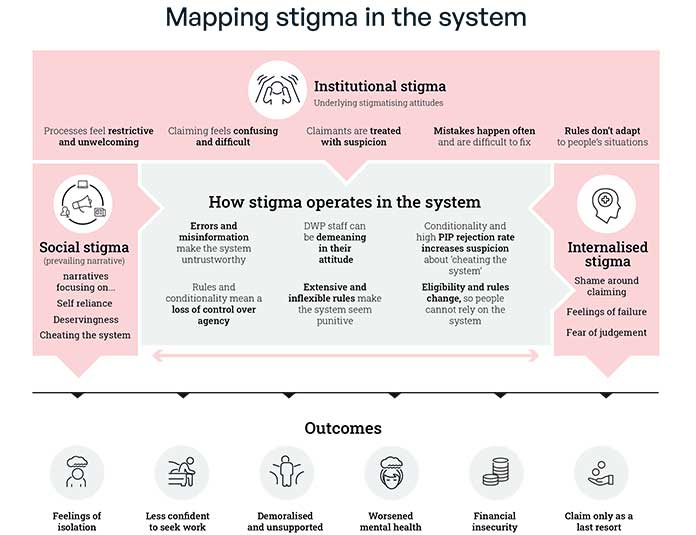

The diagram below shows how these various factors combine, to produce mechanisms by which stigma operates in the UK benefit system. These mechanisms impact both the experiences and decisions of claimants and non-claimants across the UK.

The production of self-stigma was one of the outcomes of the perceived and institutional stigma experienced within the system.

Mapping stigma in the system

Stigma and financial security

Stigma was found to discourage some individuals from applying for essential financial support, leading to financial hardship. Feelings of embarrassment, fear of judgment, and negative perceptions of the welfare system deter many from seeking help.

Some claimants feared losing control or sharing personal information. Our YouGov Survey found that 33% of claimants waited between two months and a year to claim, with 21% waiting over a year.

Delayed claims

Delaying or avoiding claiming often led to increased financial vulnerability. Many claimed benefits as a last resort after exhausting other options. One-in-five (21%) didn’t see themselves as benefit claimants, and others were deterred by negative experiences (11%) or fear of judgment (16%). 48% of those who delayed made cutbacks on non-essentials, while over one-in-five borrowed money (23%).

Welfare rights advisers highlighted links between unmanageable debt and serious financial hardship, especially when claims like PIP face lengthy delays. Some gave up on PIP applications after traumatic assessments, reapplying when they could no longer manage financially.

The emotional impact of stigma

Participants described the system as adversarial, often feeling 'helpless'. Many used words like 'fighter' or having a strong 'mindset'. Participants often felt deflated after receiving no points in their PIP assessment. One woman found the process emotionally difficult, becoming very different, much more guarded person.

The impact of stigma on health

Qualitative interviews highlighted health and emotional impact of the social security process, especially PIP. 51% of current claimants agreed that applying for benefits made their mental health worse. This rose to nearly two-thirds (64%) of those receiving PIP at the time of the survey.

The stress of applying could impact physical health, for example, as one interviewee with fibromyalgia mentioned, it is a condition ‘caused by being in flight or fight…so any stress will make it worse’.

For one man, the process exacerbated his mental health issues to the point of needing in-patient healthcare. The claimant had been employed full time until his illness, and a factor in his decline was the feeling he could not rely on the system as he expected.

In conclusion, stigma is not just a by-product, but a structural feature of the UK social security system in 2025. It is operationalised through conditionality and surveillance, reinforced through public perceptions and societal discourse, and experienced through punitive or impersonal practices.

If you have any questions about this research, please contact our Research & Learning Manager, Blanca.larrain@turn2us.org.uk

Improving the social security system

This research from the University of Bristol provides conclusive evidence that stigma is a structural feature of the UK social security system, designed into its processes and experienced in its daily operation. It lays bare the urgent need for reform built on dignity, fairness and trust.

A recurring theme is the deep-rooted lack of trust in the Department for Work and Pensions (DWP). Therefore, it is clear that to develop a more effective and sustainable social security system, the government’s ongoing reforms must focus on building trust.

Currently, accessing social security can be demoralising and infantilising, with suspicion and control undermining self-confidence and worsening health. This hampers engagement in employment support and erodes trust in assessors.

On 30 October, Turn2us will be releasing our solutions to this problem. The government has promised plans to reform employment support and the PIP assessment. However, this research makes clear that to deliver their goals, DWP must focus on rebuilding trust - moving away from a culture of control and suspicion and towards one that treats people with dignity and respect.

Our policy report will include recommendations for:

- Training for PIP Assessors and work coaches on trauma, stigma and coaching, combined with them being able to spend more time with claimants.

- Ending the reliance on infantilising sanctions and rules .

- Reforming Jobcentres and assessment centres into welcoming and supportive physical spaces.

If you would like to meet with us to discuss our developing recommendations and next steps, please reach out to our Policy Manager, Meagan.Levin@turn2us.org.uk.

About the Personal Finance Research Centre

The University of Bristol Personal Finance Research Centre is an interdisciplinary research centre exploring the financial issues that affect individuals and households, with a particular focus on low-income, marginalised or vulnerable groups.

About the authors

Sara Davies is Research Co-Director of the Personal Finance Research Centre (PFRC), University of Bristol and an Associate Professor.

Jamie Evans is a Research Fellow at PFRC.

Katie Cross is a Senior Research Associate at PFRC.